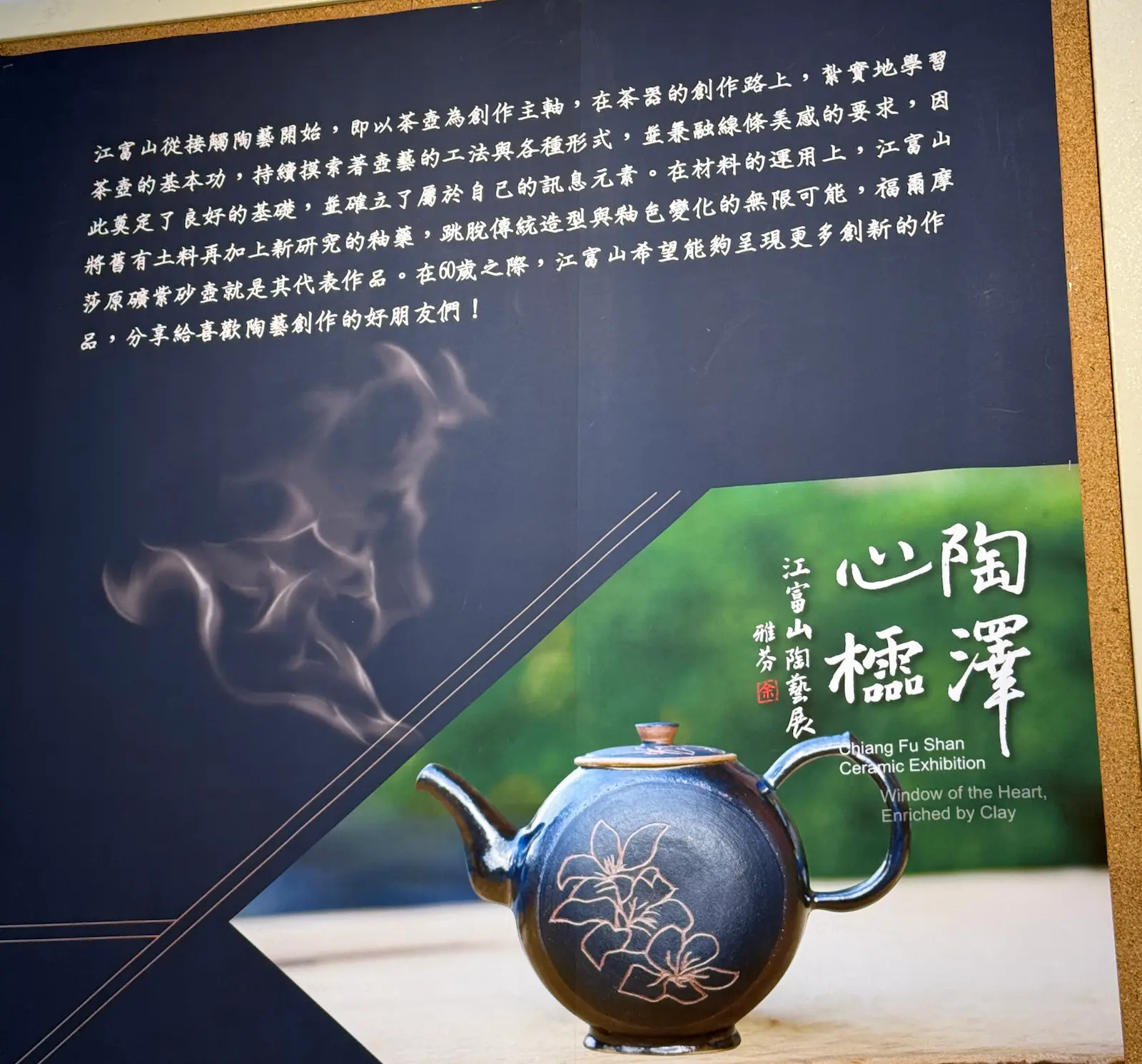

What does a teapot look like in your mind? What form does ceramic art take in your heart? Walking into Chiang Fu-shan’s “Soul Lattice & Ceramic Luster” exhibition, what meets the eye are not ordinary teapots or layers of glaze, but the integration of one of the most beautiful details of Taiwanese culture—”Window Grilles”—into the art of teapots.

This exhibition is titled “Soul Lattice & Ceramic Luster” (Xin Ling Tao Ze), taking the sound of “Lattice” (Ling) to signify the integration of window grilles and ceramic art, bringing a completely different feeling to the soul. At first, I thought it was simply drawing window grilles on ceramic pots and vases, but I later realized it was not as superficial as I had imagined.

From a surface level, drawing window grilles on a teapot requires a specific technique. Observing Chiang Fu-shan’s presentation of window grilles on teapots and vases, they are not randomly traced but appear projected, much like a texture in 3D modeling—perfectly applied, yet hand-drawn. Besides straight-line frames, there are curved drawings. Most works feature four panels with identical patterns, showing that a great deal of effort went into researching how to project them formally during the creative process.

Thinking from a symbolic perspective, window grilles are mostly ironwork. Compared to ceramic art, which is hard once fired but experienced as a warmer creative medium, the combination of these “soft” and “hard” elements creates a sense of conflict. It also allows Taiwan’s classic culture to be passed down through ceramics.

A Mechanical Background with a Ceramic Soul

During the opening ceremony, Chiang Fu-shan introduced himself as having a background in machinery. This professionalism is perfectly embodied in his work. Beyond the aforementioned formal projection of window grille patterns, what the exhibition does not show is the “craftsmanship of the teapot’s water flow.”

I remember researching tea sets before and learning that a certain group of ceramicists focuses intensely on the smoothness of a teapot’s pour. It is said that a perfect pour can make the water flow look as if it is standing still, leading many ceramicists to invest heavily in the study of water discharge.

Ultimately, this is no longer just the realm of ceramics; it belongs to the profession of mechanical engineering. Thus, Chiang Fu-shan is particularly passionate about researching the perfection of the pour and pursuing perfect symmetry in his ceramics.

Coming from a STEM background myself, I remember a teacher once saying that people with technical backgrounds are actually more likely to become obsessed with art-related fields. In Chiang Fu-shan’s work, it is easy to see that internalized mechanical soul brought into ceramic creation, becoming an ultimate pursuit of ceramic craftsmanship.

A Unique and Restrained Taste

From Chiang Fu-shan’s conversation, one discovers he is a very reserved researcher. Unlike artists who pursue the freedom of breaking frameworks, Chiang Fu-shan transforms a lifetime of precise mechanical thinking into a persistence for ceramic creation. Though I haven’t seen his studio, I can imagine there must be one or more notebooks filled with various data and CAD drawings.

This pursuit of professionalism is the key to why Chiang Fu-shan’s works become collectibles. It is not just about showing off skills, but about maintaining a paranoia for “perfection” even in places the viewer cannot see—this is exactly why his work enters the hearts of collectors.

Looking at each teapot work, I recall when I first entered the field of 3D modeling; every software had a basic teapot model. When I curiously asked the teacher why a teapot was a built-in asset in many programs, it turned out that teapots possess various curved surfaces, making them a very unique existence.

Just as window grilles are products of Taiwan’s unique culture, teapots are classic creations in the field of craftsmanship. Savoring them closely, one can more clearly understand that a tea set is not just a vessel—it is a perfect crystallization of miniature architectural spatial art and fluid mechanics.