Once clay enters the kiln, it is impossible to know what form or color the final piece will take. Beyond technique and experience, everything depends on luck; it is a sort of “mystery box,” which is part of its charm.

In January, at the Taichung Dadun Cultural Center, the opening ceremony for “Soul Lattice & Ceramic Luster” featured speeches from both ceramic circle insiders and Chiang Fu-shan’s former classmates. The former, naturally, are immersed in ceramic art; the latter, even if they do not fully understand the pottery-making process, are still happy to be “perfumed” by the art.

A retired judge said, “I believe that besides work, life needs the cultivation of art. After high-pressure work, looking at these ceramics can often help people relax.”

“Ceramic art is a dialogue between human and earth.”

At the opening ceremony, a ceramic artist in a wheelchair said, “Ceramic art is simply a dialogue between human and earth.”

Among the five elements, “Earth” represents balance, nourishment, and stability. In the natural world, earth not only exists underground to nourish every plant, but also stays on the surface to stabilize and nourish human character through “dialogue” with ceramicists and connoisseurs.

This ceramic artist’s use of the word “Earth” deepens the impression of “simplicity” associated with the ceramics world. It is not just the medium itself; ceramicists who create with this medium often give off this vibe, which can also be glimpsed through their attire. Wearing neutral, earth-toned cotton-linen outfits or Zhongshan suits, with wooden bead strands or woven bracelets on their wrists—if they also wore traditional kung fu shoes, you’d feel they could use “Qinggong” to glide effortlessly among their works. They invariably leave an impression of being “practitioners of the Way.”

The work is the author’s “spokespiece”

Switching to a “human-centric” perspective, when ceramicists handle clay, they are not merely “shaping the mud.” More importantly, they inject their intentions and thoughts into the clay, eventually allowing the ceramic to become their “spokespiece.” In this way, insiders only need to see the work to know which artist created it; it can be said that “seeing the pottery is seeing the person.”

This applies not only to ceramics but to all forms of creation; only the medium differs. Pottery, metal, leather, or even text can become a carrier for conveying intentions and thoughts. If one simply shapes an object, it is like being a production line worker without personal thought—merely “doing a tasked job” rather than “creating.”

Playing with clay to the fullest: enjoying the “glaze-temptation” of ten thousand colors

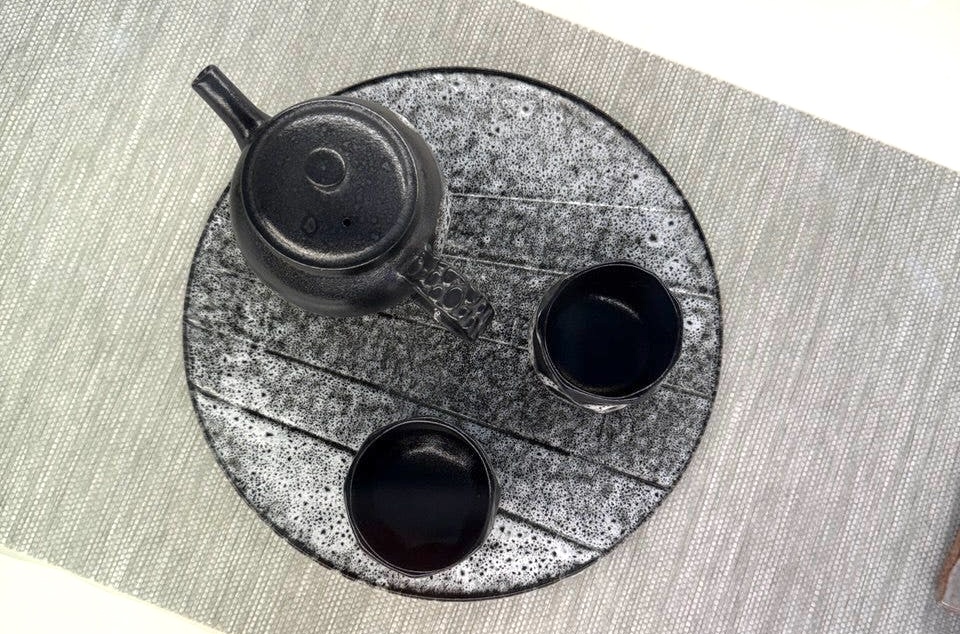

In addition to Chiang Fu-shan’s unique “Soul Lattice & Ceramic Luster” series, Chuang Pei-shan’s “Pottery Color & Glaze Temptation” series, exhibited during the same period, also caught the eyes of visitors with its unique glazes.

Most pottery is dominated by earth tones, such as reddish-brown, gray, and so on. After glazing, the most common colors are usually green, blue, or red. However, in the “Pottery Color & Glaze Temptation” exhibition, one can see many special colors like purple and lavender, with charmingly blended gradients. If the author Chuang Pei-shan had not been there in person, patiently explaining to every group of visitors, those unfamiliar with pottery might think these were common colors in the craft.

In reality, glazing pottery is not as easy as coloring on paper. The final product is often influenced by factors such as the quality of the glaze, technique, kiln temperature, atmosphere, and firing time, which cause variations in form and color.

When asked if he spent a lot of time and effort researching glaze techniques, Chuang Pei-shan smiled and said, “I’m having a blast playing with clay! I especially like making variations in the shapes!”

Perhaps it was because the author of “Pottery Color & Glaze Temptation” happened to be at the exhibition that morning, patiently introducing his precious works, which catalyzed our impulse to collect. Although he explained in the steady tone of a retired teacher, one could still sense his passion for pottery and his preference for glazing—much like a parent proudly saying, “This is the child I am proud of!”

Compared to that rare purple-smoke tea bowl, perhaps it is the light in the author’s eyes that makes one want to collect it all.